Environmentalism is in a decade-long slump. It’s increasingly hard to ignore the chorus of articles declaring the death of the environmental movement. Each international summit or national election brings with it grand pledges of action followed by complete inaction and inertia. Even at a local scale, the popular mood seems to have turned against large, sweeping changes in public transportation or conservation. One thing is for certain: the age of the big project is over.

The problem, however, is that big projects are needed more than ever. The earth is warming, perhaps catastrophically; invasive species are infiltrating the last wild places; and the recent drought in the West threatens entire population centers and global food prices. Every significant indicator of global environmental health is heading in the wrong direction. Both globally (climate change) and locally (D.C.’s combined sewer system), our environmental challenges almost certainly require complex, large-scale infrastructural initiatives; political consensus across countries and municipalities; and the public’s willingness to support massive projects. All of which now seems impossible.

Or is it? If big thinking is dead, can we leverage small, incremental actions to make a big difference?

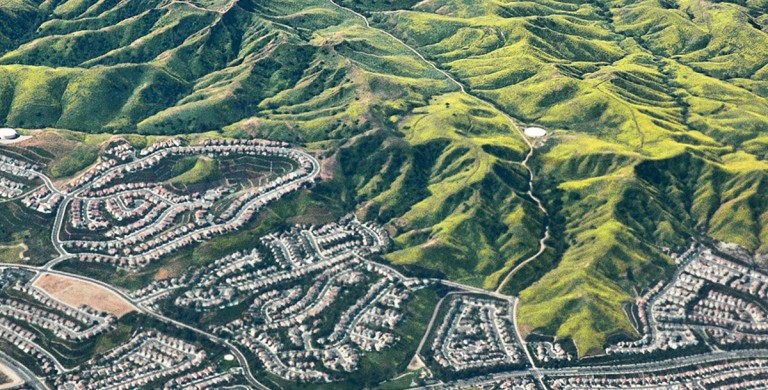

Perhaps so. Against a dark and stormy horizon, I’d like to think that there are actually glimmers of light in the cracks. To the comatose environmental movement, I’d like to make a modest proposal: consider how landscape architecture has recently approached large-scale ecological & urban issues. In the last decade, the profession of landscape architecture has begun to remake itself. Faced with the global scale of environmental challenges, landscape architects have expanded their focus from gardens, parks, and plazas to pursue bigger game: the design of cities and natural processes that shape it. Whether it is former landfill sites, water treatment facilities, or urban flood management, landscape architects have begun to address complex urban environmental issues with projects that are innovative, attractive, and functional.

If big thinking is dead, can we leverage small, incremental actions to make a big difference?

I will admit that a handful of successful projects by a relatively small profession hardly offers a panacea for the world’s environmental problems. But what is worth paying attention to is the approach taken by these projects. Instead of focusing on large global issues, the projects focus on immediate, local concerns. And the projects don’t just focus on what’s good for the environment; they focus on providing people real, tangible benefits. So in an era where big solutions to big problems seem virtually impossible, I think it’s worth focusing on a few productive strategies that show how change might happen incrementally.

1. Focus Ecology on Human Benefits

For the environmental movement to gain traction, change must be framed in terms of human benefits. Too often, modern environmentalism has pitted nature against people, framing change in the language of sacrifice. But beneficial projects don’t have to be either/or propositions; they can be both/and, linking nature and humanity for mutual benefit.

When the Chinese landscape architecture firm Turenscape designed an 84-acre wetland in the middle of a new urban district, it described the project as an “urban stormwater park.” Functionally, the park provided a wide range of ecological services such as filtering stormwater and providing habitat, but what was most enticing were the benefits to visitors. A network of paths and skywalks invited visitors to walk among the birches, providing a range of recreational and scenic benefits that also increased property values. Activist Lisa Curtis explains, “often the best way to protect wild places is to also take care of people in a way that leaves room for the wild as well.”

2. Define Problems at the Scale of the Local Site

Many polls show that when environmental issues are described as complex, global problems, people have a harder time relating to them. “Presenting frightening disaster scenarios provokes fatalism and paralysis,” writes environmental pollsters Nordhaus and Shellenberger. Yet some of those same polls show overwhelming support for green issues when they are framed as specific, local concerns.

Landscape architectural projects are, by their very nature, specific and local. They deal with a site that has distinct boundaries. This approach is by its very nature incremental. Of course, focusing on specific sites has certain disadvantages in terms of creating global change. But it does provide a model for creating change that resonates with people locally. Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates’ design for a water treatment facility outside of New Haven created a beautiful, ecologically functional project. But one of the most remarkable aspects of the project was that the utility—which was privately owned—allowed for public use of the land by adjacent neighbors, making this environmental asset also a community asset.

3. Develop Simple, Replicable Prototypes

If the public’s appetitive for mega-projects is low, is there a way to use small projects to create change? Perhaps so. If the small project is a simple, affordable prototype, then it may be able to be applied at a large scale. Take, for instance, a simple idea like a curb extension planter. These are parking-space sized bump outs that catch and filter stormwater as it flows down a street. These planters require little infrastructure or cost; they have the ability to absorb a remarkable amount of stormwater; and they help to soften and beautify a street environment. One or two of these planters would have little impact; but applied across an urban area, the impact would be huge.

This is precisely what happened this past year when New York City embarked on a 20-year, $2.4 billion project to protect local waterways using, in large part, these simple curb extension planters. Once completed, the project is expected to capture more than 200 million gallons of storm water each year. Small ideas can be big when they are scaled up.

4. Create Graphically Compelling Solutions and Narratives

Visualizing solutions helps people understand and support change. Landscape architects, like other designers, use drawings and graphics to help people understand a proposed project. When thinking about how to revive New York City’s rivers, the landscape architect Kate Orff envisioned a simple solution: oysters. Bundled into beds and sunk into city rivers, oysters suck up pollution and make dirty waters clean. Large reefs of oysters might even protect the City from future storm surges. The idea of “oyster-tecture” provided a low-tech, soft infrastructural solution that could be communicated in an understandable narrative.

Visualizing solutions helps people understand and support change. Landscape architects, like other designers, use drawings and graphics to help people understand a proposed project. When thinking about how to revive New York City’s rivers, the landscape architect Kate Orff envisioned a simple solution: oysters. Bundled into beds and sunk into city rivers, oysters suck up pollution and make dirty waters clean. Large reefs of oysters might even protect the City from future storm surges. The idea of “oyster-tecture” provided a low-tech, soft infrastructural solution that could be communicated in an understandable narrative.

Incremental change is likely not enough to address all of the ecological challenges of our times. But until the large-scale change is truly feasible, we should focus on strategies that leverage positive changes. Success breeds success, and even small projects can be a powerful weapon against the fatalism that seems to currently prevail.

January 20, 2015

Comments